Glimpse into a Badminton Boom

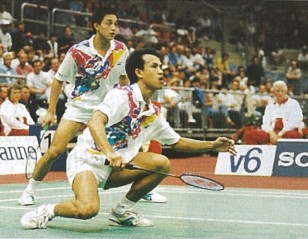

The rapid development of badminton in an Indian state with no tradition of the sport offers the opportunity for a fascinating case study. Part 1 of a two-part story:

By all accounts, badminton is booming in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu. Dozens of courts have mushroomed over the last few years in urban and semi-urban centres; thousands of players turn up for the numerous tournaments through the year; overseas coaches are hosted by private clubs. And while this might not seem exceptional in a country where badminton is a popular sport, what’s peculiar is how recent this phenomenon is in a region without a strong tradition of badminton.

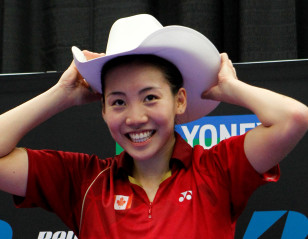

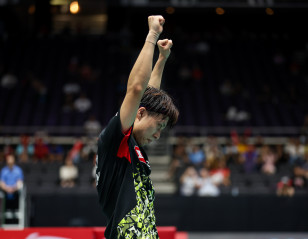

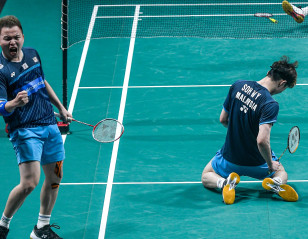

Tamil Nadu was better known for tennis (courtesy of the Amritraj brothers of the 1970s) and chess (world champion Viswanathan Anand). Badminton had little resonance beyond a few pockets. But in a phenomenon that probably merits a closer study, things changed around eight or so years ago. That meant that the first cohort of international players that emerged is still in their teens – the BWF World Junior Championships was a good example, as five players in the Indian team, including men’s singles silver medallist Sankar Muthusamy – hailed from Tamil Nadu. Emerging players include those in Para badminton – world champion Manisha Ramadass and recent winner in Brazil, Thulasimathi Murugesan.

A classic instance of the sentiment in favour of badminton is Muthusamy himself, whose father was a state tennis player. Muthusamy chose badminton over tennis, and in a sign of how committed the family is to the sport, his father quit his job to support his son. Unlike earlier players from the region who’d shift to elite academies elsewhere once they’d progressed to a higher level, Muthusamy decided to stick with the centre where he’d started (Fireball Academy in Chennai), an unusual decision given the choice of elite academies in other states, but indicative of his confidence in the quality of training available on home turf.

“My father was a tennis player; he wanted to put me in a sport. I started with tennis, and then for no particular reason I switched to badminton. From the beginning we treated it professionally. When I started around 2009, there were no courts. There were two or three courts in the whole of Chennai. Infrastructure was a problem, but now there are lots of courts. I’m quite comfortable in Chennai and I can get the training I need.”

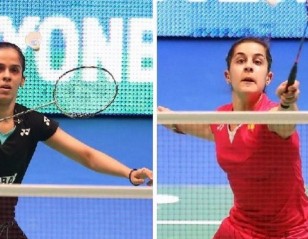

Muthusamy is not sure of the reasons for the recent explosion of interest in the sport, but credits the state association (TNBA), alongside the inspiration of watching the exploits of Saina Nehwal, Pusarla V Sindhu, Kidambi Srikanth and other Indian players.

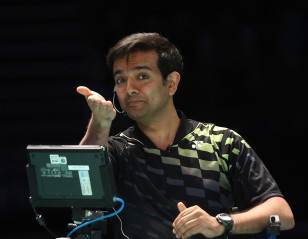

VE Arunachalam, Secretary of TNBA, reels off statistics on the health of badminton.

“There are 23 to 27 ranking tournaments a year, and six leagues played in different formats,” he says. “In Chennai (capital of Tamil Nadu) there are 200 clubs, and about 1,000 in the whole state. People who own a piece of land convert it into a court. Players are emerging from even remote villages with single courts and they do come up to the national level.

“Sponsors were interested because footfalls at tournaments have increased. We have around 30,000 participants a year, so there’s huge revenue generation. In the recent past badminton has become the No.1 sport as it can be played during any season.”

What has also changed is the profile of people taking up the sport; while it was an upper or middle income segment that played badminton earlier, it now attracts even those with lesser means.

“There are about 200 children who’ve stopped regular schooling, and have taken up badminton as a profession; they’re dedicating their lives to it. They aren’t even from well-off families. It’s so positive to see this. Then there are cases of people supporting them on a small scale,” says Arunachalam, who mentions the case of a player from a small rural community, whose village contributed to his expenses on the national circuit.

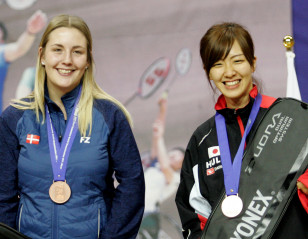

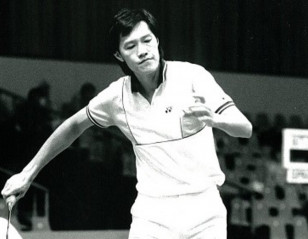

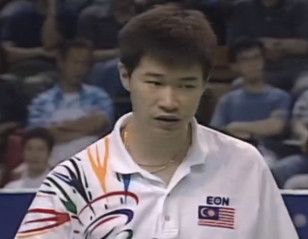

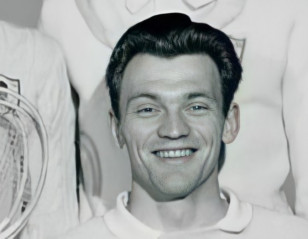

For its part, TNBA has brought in overseas coaches – including Danish legend Peter Gade and Malaysia’s Yogendran Khrishnan – to conduct clinics. “Twenty years ago, the state had only one (prominent) coach, Sanjiv Sachdeva,” says Arunachalam. “Now every year, we have three coaching clinics. We want to see an Olympian from Tamil Nadu.”

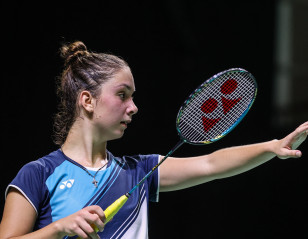

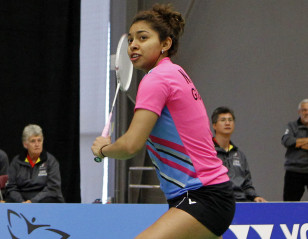

The boom in badminton isn’t restricted to the able-bodied; it is attracting differently-abled players in increasing numbers. A case in point is Para world champion Ramadass, whose story is symbolic of a wider trend. Hailing from Thiruvallur, a municipality located 50km from the capital, Ramadass started out playing several sports, but decided to focus on badminton.

“I started playing in 2015 as I idolised Nehwal,” said Ramadass. “A lot of players suddenly started playing badminton around the same time. There must be some reasons behind that. Dad believed in me, he encouraged me to dedicate myself to badminton. Initially the cost of pursuing the sport was discouraging, but we kept believing that we could achieve something. I finally got government sponsorship after five years.”

Part 2 of the story to follow

Olympic and Paralympic News

‘It’s Like Going Into Battle’ 17 April 2024

The Week in Quotes 8 April 2024

Maulana/Fikri Filled with Optimism 7 April 2024

Badminton for Peace: Transformative Projects Power #Whitecard Day 6 April 2024

‘I Thought My Career was Over’ 3 April 2024

The Week in Quotes 2 April 2024

Spain Masters: Loh Wins ‘Inner Battles’, Lands Overdue Title 1 April 2024

Breaking New Ground Thanks to Female Participation Grant 30 March 2024

The Week in Quotes 28 March 2024

Smashing Stats: Spain Masters 2024 27 March 2024

Swiss Open: Success on the Third Try 25 March 2024

No Relaxing for History-Nearing Opeyori 23 March 2024

Gideon: A Relentless Star Bids Goodbye 21 March 2024

Smashing Stats: Swiss Open 2024 20 March 2024

All England: Three-Decade Wait Ends 18 March 2024

Orleans Masters: Teen Star Miyazaki Eyes Bigger Victories 18 March 2024

All England: Nine Years On, Marin Returns to the Top 17 March 2024

All England: What a Day for Indonesia! 17 March 2024

All England: Ginting Rollercoaster, Dutch Delight 16 March 2024

All England: Christo Popov Sets French Milestone 15 March 2024

All England: Injured Jia Tests Her Resolve 15 March 2024

All England: Christie Finds Elusive Form 15 March 2024

All England: Olympic Race Adds Edge to Opening Round 14 March 2024

All England: An Injury Scare, A Passing Cloud 13 March 2024

All England: Defending Champ Falters in Opening Test 12 March 2024

Smashing Stats: All England 2024 12 March 2024

All England: Axelsen Seeks Year’s First Title 12 March 2024

French Open: ‘If An Se Young Can, So Can We’ 11 March 2024

French Open: An Se Young’s Reign Continues 10 March 2024

French Open: High-Flying Lee/Yang in Final 10 March 2024

French Open: Old Demons Return to Haunt Tai Tzu Ying 9 March 2024

French Open: Trust Builds the Bond 8 March 2024

International Women’s Day: Nixey Breaking Barriers in Badminton 8 March 2024

French Open: ‘I Need to Start from Zero Again’ 6 March 2024

French Open: Hirota Makes Tentative Return 5 March 2024

Smashing Stats: French Open 2024 5 March 2024

French Open: A Dream Gets Closer 5 March 2024

Shuttle Time Helps Counter Drug Abuse in Sierra Leone Communities 2 March 2024

‘There’s Much More in Our Tank’ 1 March 2024

Tai Tzu Ying, The Second Coming 29 February 2024

Smashing Stats: German Open 2024 28 February 2024

Para World Champs: Cheah Puts Ghost to Rest 24 February 2024

Para World Champs: Season of Promise for De Marco 22 February 2024

Para World Champs: A Special Moment for Jamporn 21 February 2024

Para World Champs: Faith, Paris Kept Kohli Going 21 February 2024

Para World Champs: Yang’s Speed Floors Seeded Ramli 20 February 2024

In a Class of Her Own 17 February 2024

Wiser Chyrkov Aims Higher 16 February 2024

Take Two, with New Mates 15 February 2024

Aranguiz Finds His Fit 14 February 2024

Kang & Seo: Showcasing Winning Ability 12 February 2024

Ginns Races to Rack Up Points 11 February 2024

Yeo Jia Min: The Graph Rises Again 10 February 2024

Small Town Boy Dreams Big 9 February 2024

Paris Dreaming 8 February 2024

Sprint Begins 7 February 2024

The Week in Quotes 6 February 2024

Humans of Shuttle Time: Paulo Jerome Niniano Quidato 1 February 2024

The Week in Quotes 31 January 2024

Smashing Stats: Thailand Masters 2024 30 January 2024

Indonesia Masters: Immortality Unlocked 28 January 2024

Indonesia Masters: Marthin Eager to Seize Chance 28 January 2024

Indonesia Masters: Three Events, Three Finals 27 January 2024

Indonesia Masters: Istora Fairytale in Motion 26 January 2024

Indonesia Masters: Qualifier George Stops Lu 25 January 2024

Smashing Stats: Indonesia Masters 2024 23 January 2024

Malaysia Open: Trio Blaze a Trail 14 January 2024

Malaysia Open: Second Bite at Cherry 14 January 2024

Malaysia Open: Here and Now Zhang/Zheng’s Priority 13 January 2024

Malaysia Open: Lin Relishing ‘Axiata Luck’ 13 January 2024

Malaysia Open: Super Singaporeans March On 12 January 2024

Malaysia Open: Iwanaga/Nakanishi Thump Another Barrier 11 January 2024

Malaysia Open: ‘Anything is Possible’ 10 January 2024

Malaysia Open: Happy Hitting Shuttles Again 9 January 2024

Game for Friendly Fight 5 January 2024

The Quest for Paralympic Gold 3 January 2024

2023 in Review: An-Precedented Phenomenon 30 December 2023

Debut Season Thrills Para Badminton Newcomers 29 December 2023

2023 in Review: Big Breakthroughs 27 December 2023

2023 in Review: China’s Year to Celebrate 26 December 2023

2023 in Review: Memorable Upsets 25 December 2023

2023 in Review: That Taste of Glory Reappears 24 December 2023

Looking Back: ‘It’s Been Splendid’ 23 December 2023

YOG Legacy Plan: Catalyst for African Badminton Development 21 December 2023

Smashing Stats: World Tour Finals 2023 12 December 2023

Empowering Dreams: BWF-IPC Para Badminton Workshop Ignites Passion and Possibilities in Africa 3 December 2023

Dorsa Yavarivafa: A Refugee’s Journey of Olympic Dreams 15 November 2023

UAE Badminton in the Spotlight 10 November 2023

Rosengren ‘Positive and Happy’ After Malaysia Stint 9 November 2023

The Week in Quotes 8 November 2023

Smashing Stats: Korea Masters 2023 7 November 2023

HYLO Open: Four Years of Hard Work Rewarded 6 November 2023

Asian Para Games in Pictures 4 November 2023

Smashing Stats: HYLO Open 2023 1 November 2023

French Open: ‘This One’s For You’ 30 October 2023

French Open: ‘We Cracked the Code’ 29 October 2023

French Open: Tang/Tse on Cloud Nine 28 October 2023

French Open: Idol Conquered, Ohori Basks in ‘My Moment’ 28 October 2023

French Open: ‘Badminton is a Mental Game’ 27 October 2023

100 Consecutive Weeks as No.1 for Axelsen 26 October 2023

French Open: Hong Kong China Mixed Pairs Impress 25 October 2023

BWF Presents Super Smash Squad: Unleashing Badminton Heroes 25 October 2023

French Open: ‘We Really Wanted It’ 24 October 2023

Denmark Open: Second Best No More 23 October 2023

Denmark Open: ‘This Time, I Won’t Let It Go Easily’ 22 October 2023

Denmark Open: Oozing Charm in Odense 22 October 2023

Denmark Open: One More Final for Mentality Monster 22 October 2023

Denmark Open: Keep Calm and Play On 21 October 2023

Denmark Open: ‘Arctic Outing’ Sparks Iwanaga/Nakanishi 21 October 2023

Denmark Open: ‘Not a Tiger, I’m a Wolf’ 21 October 2023

Denmark Open: Titans Tai, Marin in Duel No.22 20 October 2023

Denmark Open: ‘Absolutely Crazy’ 19 October 2023

Denmark Open: FajRi ‘Trying to Recapture Winning Feeling’ 18 October 2023

Denmark Open: Lamsfuss Playing Without Painkillers Again 18 October 2023

Denmark Open: Toma’s Front Court Aggression Pays Off 17 October 2023

Smashing Stats: Denmark Open 2023 16 October 2023

Arctic Open: Feng/Huang Going Great Guns 16 October 2023

Arctic Open: ‘I Never Lost Faith’ 15 October 2023

Arctic Open: Malaysia Secure Men’s Singles Title, Unique Feat 15 October 2023

Arctic Open: Style Change Lifts Chochuwong Past Tai 13 October 2023

Arctic Open: ‘Nice to Play on a Friday’ 13 October 2023

Arctic Open: Czech Mates Get Dream Daddies Date 12 October 2023

Arctic Open: Man/Tee Focused on Task Ahead 12 October 2023

Arctic Open: Debut to Treasure 11 October 2023

Arctic Open: Revenge Mission Accomplished 11 October 2023

Top Ranking for Satwik/Chirag, Reward for Intensity 10 October 2023

World Mental Health Day: Navigating the Tricky Game of Recovery 10 October 2023

Asian Games: China, Korea Set Up Uber Cup Final Repeat 30 September 2023

Asian Games: Korea Win High-Stakes Battle 29 September 2023

Asian Games: Korea Oust Malaysia 28 September 2023

Huhn’s Honour to Cherish for Life 22 September 2023

‘Ego Held Us Back’ 20 September 2023

The Week in Quotes 19 September 2023

Hong Kong Open: Decades-Old Droughts Smashed 17 September 2023

Hong Kong Open: History Beckons Tang/Tse 17 September 2023

Hong Kong Open: Enjoyment Reappears for ‘Danish Daddies’ 16 September 2023

Hong Kong Open: Zhang on the Right Track 16 September 2023

Hong Kong Open: Go, Jin Wei! 16 September 2023

Hong Kong Open: It’s All About Shuttle Control 15 September 2023

Hong Kong Open: Danes Dazzle 14 September 2023

Hong Kong Open: Blessed Restart for Lamsfuss/Lohau 14 September 2023

Hong Kong Open: Local Stars Bask in Home Love 14 September 2023

Hong Kong Open: Ng, Popov Play Spoilers 13 September 2023

Hong Kong Open: ‘Must Start Winning Second Rounds’ 12 September 2023

Smashing Stats: Hong Kong Open 2023 12 September 2023

Smashing Stats: China Open 2023 5 September 2023

Happy Ground China | Zheng/Huang 3 September 2023

Raul Anguiano Paving New Paths in Sports Management 2 September 2023

The Week in Quotes 30 August 2023

French Prodigy Lefort a Real Prospect at Home Paralympics 29 August 2023

Seo-l Stirring Day for Korea 28 August 2023

View From The Top 28 August 2023

‘Gen Next’ Face-off, and a Battle for the Ages 27 August 2023

Kim & Anders Carry Danish Hopes 27 August 2023

#Copenhagen2023: Day 5 in Quotes 26 August 2023

Post-Injury Medal, Marin’s Triumph of Grit 26 August 2023

Prannoy Dares, Prannoy Wins 25 August 2023

#Copenhagen2013: Day 4 in Quotes 25 August 2023

#Copenhagen2023: Day 3 in Quotes 24 August 2023

‘Felt I Got Hit by a Truck’ 23 August 2023

#Copenhagen2023: Day 2 in Quotes 23 August 2023

As Okuhara and Pusarla Clash, Hope and Despair 23 August 2023

Popovs at Ease With Double-Tasking 22 August 2023

#Copenhagen2023: Day 1 in Quotes 22 August 2023

Ten Years of the World Championships – and a First Win 21 August 2023

Familiar Turf, But Conditions Apply 20 August 2023

Generation That Ygor Coelho Inspired Has Arrived 20 August 2023

Three From Time: Denmark’s Home Champs 19 August 2023

Did You Know? In Copenhagen, Korea Rule Men’s Doubles 18 August 2023

Vitidsarn Adding Weapons to Arsenal 17 August 2023

‘You Cannot Compare Yourself With Others’ 16 August 2023

‘Have to Forget the Past and Move On’ 15 August 2023

Flashback: Copenhagen 2014 and the Crowning of Carolina 14 August 2023

Meet the Breakdancer-Turned-Para Shuttler 13 August 2023

Presentations on the Art and Science of Competing 11 August 2023

Australian Open: Beiwen Snaps Blip on Surgery Anniversary 6 August 2023

Australian Open: Prannoy Savours ‘Special Year’ 5 August 2023

4 Nations Para: Helle High on Life After Breakthrough Win 5 August 2023

4 Nations Para: Paris Love Story Inspiring Rogerio and Edwarda 5 August 2023

4 Nations Para: Master Morten Amazed 4 August 2023

Smashing Stats: Australian Open 2023 1 August 2023

Paris 2024: With a Year to Go, Festive Spirit Pervades 26 July 2023

Smashing Stats: Japan Open 2023 25 July 2023

Badminton Lets Pu Gui Yu Enjoy the World 20 July 2023

Smashing Stats: Korea Open 2023 19 July 2023

US Open: Moving Ahead as One 17 July 2023

US Open: Pace the Name of Katethong’s Game 16 July 2023

US Open: Terrific Teens Ignite American Dream 15 July 2023

US Open: ‘Desperate’ Gao Frustrates Pusarla 15 July 2023

US Open: Seeing Double Double? 14 July 2023

US Open: Nguyen’s Time to Shine 14 July 2023

US Open: ‘My Son Keeps Me Going’ 14 July 2023

US Open: ‘It’s Like a Dream’ 13 July 2023

US Open: Ready to Go Again 12 July 2023

US Open: Pursuing Short-Term Goals for Long-Term Success 12 July 2023

Smashing Stats: US Open 2023 12 July 2023

Canada Open: ‘Great Week for Danish Men’s Doubles’ 10 July 2023

Canada Open: Final Finally ‘Feels Right’ 9 July 2023

Canada Open: ‘Net Rhythm’ Lifts Sen 9 July 2023

Schaefer, Wilson and a Quest for Sustainability 7 July 2023

‘She Feels Almost Like Another Student’ 6 July 2023

World Badminton Day: Initiatives that Power Spread of Badminton 5 July 2023

No Hall, No Problem: Meet the Shuttle Time Tutor Firing Up Fiji 5 July 2023

Smashing Stats: Canada Open 2023 4 July 2023

How Cordon’s Inspiring Latin America’s Badminton Bloom 4 July 2023

New Kid on the Block Makes his Mark 3 July 2023

Vittinghus & Istora: A Special Relationship 2 July 2023

Lakshya Finding Way Back After Nose Surgery 29 June 2023

Two Olympic Champs Aiding Weng’s Growth 28 June 2023

Female Participation Grant Gives Space-Loving Nazaha Out-of-World Experience 27 June 2023

Action, Fun and Laughter 27 June 2023

Special Olympics: Gade, Zwiebler Shine Light on Inclusion 26 June 2023

Asian Qualifier: Best Friends Steer Hong Kong China to Bali 26 June 2023

Let’s Move, Let’s Shuttle Time for Olympic Day 23 June 2023

‘Let’s Move’ the An Se Young Way 23 June 2023

Badminton Goes All-Inclusive at Special Olympics World Games 22 June 2023

Smashing Stats: Taipei Open 2023 20 June 2023

World Refugee Day: Growing Through the Olympic Experience 20 June 2023

Entries Confirmed for ANOC World Beach Games Asian Qualifier in Malaysia 20 June 2023

Smashing Stats: Indonesia Open 2023 13 June 2023

Singapore Open: Hoki/Kobayashi’s ‘Stubbornness’ Vindicated 12 June 2023

Singapore Open: ‘Our Year’ 11 June 2023

Singapore Open: Vibing at ‘Home Away From Home’ 11 June 2023

Singapore Open: Baek/Lee Train Rolls On 10 June 2023

Singapore Open: ‘Makes No Sense I’m Playing This Well’ 10 June 2023

Singapore Open: ‘Ambitious’ Koreans Trip Zheng/Huang 9 June 2023

Singapore Open: ‘Starting Point’ That Made Naraoka Believe 8 June 2023

Singapore Open: Christo Snatches Loh’s High 8 June 2023

Singapore Open: Desiring Reward for Consistency 7 June 2023

Singapore Open: ‘I’m Going to Come Back Stronger’ 6 June 2023

Singapore Open: En Route to Fast Lane 6 June 2023

Smashing Stats: Singapore Open 2023 6 June 2023

Zhang & Wang: Stars With Different Legacies 4 June 2023

Chen Long: Consistency Personified 2 June 2023

Smashing Stats: Thailand Open 2023 30 May 2023

Malaysia Masters: Fighter Prannoy Completes Rerise 28 May 2023

Malaysia Masters: Project Paris 2024 Activated 27 May 2023

Malaysia Masters: Adinata Relishes Flying Indonesian Flag 26 May 2023

Malaysia Masters: Kidambi to Keep Plugging Away 25 May 2023

Two Icons Walk Into Hall of Fame 25 May 2023

Malaysia Masters: Definite-Li Doable 24 May 2023

Smashing Stats: Malaysia Masters 2023 23 May 2023

Sweet 13th for China! 21 May 2023

Flawless Korea Overcome Malaysian Challenge 20 May 2023

Taekwondo Champ Li Shi Feng Aces Celebration 18 May 2023

Emotional Return to Birthplace for Adam Dong 15 May 2023

Minnows Hope to Make a Mark 13 May 2023

Thai Para: Fast Friends Zooming Forward Together 13 May 2023

Back in Badminton Heartland! 13 May 2023

‘Fukuhiro’ High on Confidence After Dubai Win 12 May 2023

The Sudirman Cup Story 12 May 2023

Group D Preview: Japan, Korea Will be Wary of France 11 May 2023

Thai Para: The Next Generation 10 May 2023

The Week in Quotes 9 May 2023

Glimpse into a Badminton Boom | Part II 7 May 2023

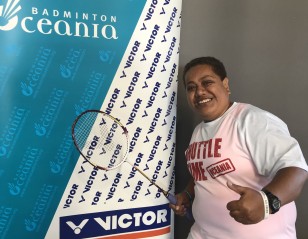

Humans of Shuttle Time: Josefa Matasau 6 May 2023

Group C Preview: The Group of Death? 5 May 2023

Simon’s Eyes Set on Paris 2024 4 May 2023

The Week in Quotes 3 May 2023

The Week in Quotes 25 April 2023

Vitidsarn’s Drive Inspires Chaiwan 24 April 2023

New Ace in the Pack for China 22 April 2023

Group B Preview: Tunjung’s Form Bodes Well for Indonesia 21 April 2023

Big Dreamers in Perfect Sync 19 April 2023

The Week in Quotes 18 April 2023

Plato to English, How He Bing Jiao is Breaking Barriers 16 April 2023

Group A Preview: Decisive Denmark-Singapore Clash 14 April 2023

Fast-Rising Duo Give Edge to India’s Hopes 13 April 2023

The Week in Quotes 11 April 2023

Female Participation Grant Realises Quintet’s Ambitions 8 April 2023

The Week in Quotes 5 April 2023

Smashing Stats: Orleans Masters 2023 4 April 2023

Aspiring Athletes Grateful for Scholarship Opportunity 3 April 2023

Humans of Shuttle Time: Richard Gregory Wong 1 April 2023

The Week in Quotes 29 March 2023

Smashing Stats: Spain Masters 2023 28 March 2023

Swiss Open: Chou Breaks the Shackles 26 March 2023

Video: The Colourful Career of Goh Liu Ying 23 March 2023

The Week in Quotes 22 March 2023

Smashing Stats: Swiss Open 2023 21 March 2023

All England: Lee Hopes to Discover Lost Confidence 17 March 2023

Smashing Stats: All England 2023 14 March 2023

The Week in Quotes 13 March 2023

Happy Ground England | Watanabe 12 March 2023

Hip Fixed, Ellis Out of Tight Spot 11 March 2023

Chen/Jia ‘Not Afraid to Start From Zero Again’ 10 March 2023

Friendship, Form Steer Lane/Vendy 9 March 2023

International Women’s Day: ‘Badminton a Universal Recipe for Happiness’ 8 March 2023

International Women’s Day: Haendel Ling, with Love, Passion and Care 8 March 2023

The Week in Quotes 7 March 2023

Smashing Stats: German Open 2023 7 March 2023

When Shida Turned a One-Assignment Reporter 4 March 2023

The Week in Quotes 28 February 2023

Para Shuttlers’ Road to Paris Begins in Spain 18 February 2023

The Week in Quotes 13 February 2023

Confident, Positive and on Track 12 February 2023

The Week in Quotes 8 February 2023

Sankar Muthusamy: Seeking to Build on Junior Success 6 February 2023

Humans of Shuttle Time: Robbert de Keijzer 3 February 2023

Boost to Para badminton with Inclusion at LA 2028 Paralympic Games 1 February 2023

The Week in Quotes 30 January 2023

Malaysia Open: ‘Not Three Hours, Please’ 15 January 2023

Malaysia Open: Liew Enters Main Draw 9 January 2023

Hunter to Hunted 8 January 2023

Best Yet to Come: Ong & Teo 7 January 2023

Looking Back: Cream Savours Indian Gold 6 January 2023

Chou Sets Three Main Targets 5 January 2023

Bumper Season Ahead! 3 January 2023

2022 in Quotes | Part II 2 January 2023

2022 in Review: Back with a Bang! 31 December 2022

2022 in Review: A Year to Savour for India 29 December 2022

2022 in Review: Memorable Year for Korean Badminton 28 December 2022

2022 in Review: Winning Smiles Return 27 December 2022

2022 in Quotes | Part I 26 December 2022

It’s Not About Results, Says Christie on 2022 25 December 2022

Dislike to Discovery, Matias’ Love Affair with Badminton 24 December 2022

‘Extraordinary Year’ for Dual Paralympian Mathez 23 December 2022

Looking Back: Thinaah’s ‘Do-Or-Die’ Transition from Singles 21 December 2022

The Week in Quotes 20 December 2022

Olympic Champion Mum Kim’s Inspiration 19 December 2022

Grateful to Badminton, Gaitan Eager to Give Back 18 December 2022

Pink & EQ – Thailand’s Exciting Next-Gen 17 December 2022

Wong Wing Ki Embarks on New Journey 15 December 2022

The Week in Quotes 14 December 2022

Preview: An Even Field in Men’s Doubles 4 December 2022

Meet the Debutants 3 December 2022

Axelsen’s North American Show Thrills Fans 28 November 2022

BWF Player of the Year Awards 2022 Nominees 28 November 2022

The Week in Quotes 21 November 2022

The Week in Quotes 16 November 2022

French Open: At Long Last, Party in Paris 31 October 2022

French Open: 105 Per Cent Ready 30 October 2022

French Open: He Finally Gets Her Way 30 October 2022

French Open: ‘Ridiculous’ Fighting Spirit Rewarded 29 October 2022

French Open: ‘I Want to be Champion’ 29 October 2022

French Open: Not Here to Make Up Numbers 29 October 2022

French Open: My Turn, Says Intanon 28 October 2022

French Open: Character Trumps ‘Best Pair of 2022’ 28 October 2022

French Open: Maiden Home Win Boosts History Chasers 27 October 2022

Feeling the Pressure, Admits Lanier 27 October 2022

French Open: Solid Defence Propels Rhustavito 26 October 2022

French Open: Lit Arena Ignites Satwik/Chirag’s Diwali 26 October 2022

‘Pink’ Pitchamon to Play in Grandfather’s Honour 26 October 2022

French Open: Cherishing Second ‘First Win’ 25 October 2022

‘I Haven’t Seen My Parents for Three Years’ 25 October 2022

Denmark Open: ‘I was Close to Tears’ 24 October 2022

Denmark Open: Alfian/Ardianto Not Stopping at Four 23 October 2022

Denmark Open: Shi’s All That 23 October 2022

Denmark Open: Another Partner, Another Final 22 October 2022

Denmark Open: Lee Awaits Spoiler Loh 22 October 2022

Denmark Open: Intanon Invincible in Odense 22 October 2022

Denmark Open: ‘We Stopped Talking for a Day’ 21 October 2022

Denmark Open: Best Still to Come, Says Huang 20 October 2022

Denmark Open: Marthin/Carnando Settle Score 20 October 2022

Denmark Open: A Week’s Enough for Lee and Baek 19 October 2022

Denmark Open: ‘I’m Glad She Waited for Me’ 19 October 2022

Denmark Open: Bay/Mølhede Bask in ‘Biggest Win Ever’ 19 October 2022

Denmark Open: ‘Like She Was Never Away’ 18 October 2022

Ukraine’s Youngsters Continue to Nurse Badminton Dreams 18 October 2022

The World Juniors: A Window into the Future 16 October 2022

Blichfeldt Turns to Nature to Prepare for Home Event 15 October 2022

Choong Ready to Take on the World 13 October 2022

The Week in Quotes 11 October 2022

World Mental Health Day: ‘I Woke Up 20 Times an Hour’ 10 October 2022

World Mental Health Day: Badminton Joy for Orphans 10 October 2022

From Gang Member to African Champion 6 October 2022

How Shi Got His Groove Back 5 October 2022

Dad, Mum, Badminton 4 October 2022

The Week in Quotes 3 October 2022

Turning Dreams to Reality 2 October 2022

‘We are a Promising Pair’ 1 October 2022

Destination Copenhagen 2023 29 September 2022

The Week in Quotes 26 September 2022

The Week in Quotes 19 September 2022

Humans of Shuttle Time: Danny Ten 16 September 2022

Yvonne & Iris, the Unlikely Pair 13 September 2022

The Week in Quotes 12 September 2022

Julien Paul’s Backup Plan 11 September 2022

Multiple Paralympic Medallist Czyz Explores Badminton’s Beauty 10 September 2022

In Midst of Busy Season, Elgamal Pursues Academic Goals 8 September 2022

The Week in Quotes 7 September 2022

Badminton Community Mourns Passing of Jeff Robson 6 September 2022

Japan Open: ‘This is Why We Play Badminton’ 5 September 2022

Japan Open: Three the Magic Number 4 September 2022

Japan Open: Liang & Wang ‘Fired Up’ for Final 4 September 2022

Japan Open: In Kento’s Absence, Kenta Steps Up 3 September 2022

Japan Open: Kidambi, Wardoyo Savour Big Scalps 31 August 2022

Pusarla Withdraws From World Championships 15 August 2022

Appenzeller Hoping to Inspire the Next Generation of Youth 12 August 2022

Gilmour Experiences Only Positive Vibes After Coming Out 10 August 2022

Commonwealth Games: Australians Overcome Jamaican Challenge 5 August 2022

Return of Istora Fan Mania 26 July 2022

The Week in Quotes 25 July 2022

AirBadminton Takes Off In Hamburg 20 July 2022

Singapore Open: ‘My Form is Back’ 17 July 2022

Singapore Open: Pusarla Celebrates ‘Extra Special’ Title 17 July 2022

Singapore Open: ‘Nothing to Lose’ for Gutama/Isfahani 16 July 2022

Singapore Open: Naraoka Ignores Rankings to March On 15 July 2022

Malaysia Masters: ‘I Don’t Want to Stop Here’ 9 July 2022

Malaysia Masters: Rising Youngsters Stay Grounded 8 July 2022

Malaysia Masters: Momota Refuelling Reserve Tank 8 July 2022

World Badminton Day: ‘Best Seat in the House’ 6 July 2022

Malaysia Open: ‘Brilliant to be Here’ 28 June 2022

The Week in Quotes 27 June 2022

Liliyana Natsir – Front Court Maverick 25 June 2022

Polii: Olympics Taught Me to Never Give Up 23 June 2022

Olympic Day: Rossi’s Paris 2024 Journey Begins Now 23 June 2022

World Refugee Day: Shuttle Time For Peace 20 June 2022

World Badminton Day: Better Health Through Badminton 19 June 2022

Polii Bids Emotional Farewell 12 June 2022

Fanatics of TotalEnergies | Episode 1: Bangkok Edition 8 June 2022

BWF Female Participation Grant 2022: Salo Aims High 5 June 2022

More To Come From Olympic Champions 4 June 2022

Adcocks Loving Life with Baby Penelope 3 June 2022

The Week in Quotes 31 May 2022

BWF Female Participation Grant 2022: Mellberg Rejects Mediocrity 28 May 2022

How An Se Young Powered Korea’s Fightback 21 May 2022

Another Arrow to Mathias’ Bow 20 May 2022

‘What a Day for Indian Badminton’ 16 May 2022

‘Best Moment of My Career’ 14 May 2022

Ginting: Captain Setiawan a Great Support 13 May 2022

Chou and Co ‘Fighting’ for Elusive Semis Spot 12 May 2022

The Week in Quotes 21 April 2022

The Week in Quotes 11 April 2022

World Health Day: Pick Up a Racket and Get Active 7 April 2022

Raise Your #WhiteCard For Peace in Sport 6 April 2022

The Week in Quotes 4 April 2022

Otoase Talks Badminton and Autism 2 April 2022

Smashing Stats: YONEX All England Open 2022 16 March 2022

Spanish Para I: Ramli Nets Double, English Stars Bounce Back 14 March 2022

World Badminton Day: The Past Guides the Future 9 March 2022

International Women’s Day: Female Participation Grant Breaks New Ground 8 March 2022

International Women’s Day: Xu Gives Back to Badminton 8 March 2022

Spanish Para II: Newcomer Surreau Sizzles 6 March 2022

First World Badminton Day to be held 5 July 2022 4 March 2022

Spanish Para II: Debutants Set to Dazzle 1 March 2022

‘Greatest Year Ahead’ for Joshi 27 February 2022

Spanish Debut a Surreal Moment for Newbie Surreau 26 February 2022

The Week in Quotes 22 February 2022

The Week in Quotes 15 February 2022

‘Asian Leg Was My Wake-Up Call’ 13 February 2022

The Week in Quotes 8 February 2022

World Championship Title Boosts 2022 Aims for Popor 3 February 2022

BWF Unveils Para Badminton Initiatives for 2022 31 January 2022

The Week in Quotes 25 January 2022

The Week in Quotes 17 January 2022

Inclusion on Forbes List Will Encourage Youngsters, Says Sindhu 14 January 2022

Seven Players Test Positive To COVID-19 at YONEX-SUNRISE India Open 2022 13 January 2022

Female Participation Grant Empowers Ngoma and Many More 10 January 2022

Stoliarenko Balances Three Loves: Badminton, Travel, Art 6 January 2022

Always Reddy: Sikki’s Special Friendship with Indonesian Fan 5 January 2022

Video: Secret to Denmark’s Badminton Success 4 January 2022

2021 in Quotes | Part II 3 January 2022

2021 in Review: Newcomers Tahiti Add Freshness, Colour 28 December 2021

2021 in Quotes | Part I 27 December 2021

2021 in Review: Tokyo Olympics by Numbers 26 December 2021

Tinomana Naea Recognised For Serve-ing Pacific 22 December 2021

The Week in Quotes 21 December 2021

50 Battles and Counting for Super Sapsiree 6 December 2021

Vitidsarn not Burdened by Ponsana Legacy 4 December 2021

Indonesia Open: Imperious Axelsen Nets Rare Record 29 November 2021

Bali Badminton Festival: A Bonanza of Gifts 22 November 2021

Indonesia Masters: How Popov Battled ‘Demons and Shadows’ in Opener 17 November 2021

Indonesia Masters: Home is Where Jordan’s Heart is 15 November 2021

Li Jun Hui and Kolding Bid Goodbye 15 November 2021

Loh of Losing Luggage to High of Winning 13 November 2021

Seven Weeks of Learning, Adapting on the Road 12 November 2021

The Week in Quotes 9 November 2021

The Thomas Cup Story, as Recalled by an Icon 7 October 2021

England Geared to Spark in Vantaa 25 September 2021

Meet Elias, Tahiti’s 14-Year-Old Sudirman Cup Starlet 22 September 2021

Sudirman Cup Offers Praneeth Fresh Start 21 September 2021

The Week in Quotes 13 September 2021

Tokyo 2020: Para Badminton in Stats 12 September 2021

One Week, Two Dreams Come True 10 September 2021

Para Badminton at Tokyo 2020 in Quotes | Part II 7 September 2021

Para Badminton at Tokyo 2020 in Quotes | Part I 6 September 2021

Tokyo 2020: Para Badminton In Numbers 1 September 2021

Para Shuttler Leva Targets Javelin Medal in Tokyo 27 August 2021

#RaiseARacket for Your Heroes These Tokyo 2020 Paralympics 24 August 2021

BWF Collaborates on Promoting Leadership Roles for Women 22 August 2021

Moore and Mairs’ YouTube Channel Flying High 16 August 2021

Tokyo 2020 in Numbers 7 August 2021

Sir Craig Reedie Awarded President’s Medal 5 August 2021

Win or Lose, Nguyen Wants to Do Migrant Parents Proud 28 July 2021

Tokyo 2020: A Parliamentarian at the Olympics 22 July 2021

Olympic Legacies: Immortality Awaits Evergreen Setiawan 21 July 2021

Olympic Legacies: Top Seeds Who Struck Gold 20 July 2021

#RaiseARacket for Your Heroes These Tokyo 2020 Olympics 19 July 2021

Road to Tokyo: Paved with Friendship and Inspiration 18 July 2021

Olympic Legacies: Unseeded Gold Medal Winners 18 July 2021

Olympic Legacies: Will the ‘Famous Eight’ Add a Ninth Member? 17 July 2021

Road To Tokyo: Bumpy Journey but No Regrets 16 July 2021

Road to Tokyo: For Spain and for Marin 15 July 2021

Road to Tokyo: ‘Everyone’s in the Same Boat’ 12 July 2021

Road to Tokyo: Ng’s Du-ing Just Fine 11 July 2021

Road to Tokyo: All About Keeping It Simple 10 July 2021

Road To Tokyo: ‘Not Going to Japan to Have Fun’ 9 July 2021

The Week in Quotes 6 July 2021

Road to Tokyo: Japan Sweet Japan for Koreans 4 July 2021

20 Days to Tokyo 2020: Men’s Singles Dark Horses 3 July 2021

Road to Tokyo: Life Only Gets Better for Axelsen the Gold Hunter 29 June 2021

The Week in Quotes 28 June 2021

Olympic Legacies: Most Medals in the Bag 27 June 2021

Road to Tokyo: Goh Blazes Trail for Malaysia 25 June 2021

Did You Know? Ahsan’s Best Olympic Run Wasn’t With Setiawan 24 June 2021

Olympic Day: My First Olympics 23 June 2021

How Player Development Grants Help Create Potential Olympians 23 June 2021

The Week in Quotes 21 June 2021

World Refugee Day: ‘Badminton Joy Spread Like Light’ 20 June 2021

Meet Paniz, Whose ‘Parallel Play’ is Making History 19 June 2021

Cai Yun and Fu Haifeng, Indomitable Spirit 15 June 2021

Badminton Community Bids Farewell to Kido 15 June 2021

The Week in Quotes 14 June 2021

On This Day: England Defy Odds, Deny Malaysia 11 June 2021

Zhang Ning, Trail-Blazer 9 June 2021

The Week in Quotes 7 June 2021

On This Day: Badminton Becomes Olympic Sport 5 June 2021

The Week in Quotes 31 May 2021

Promising Talent Rachel Chan Brightens Canada’s Horizons 30 May 2021

‘Bello Will Always be My Biggest Inspiration’ 29 May 2021

Russian Duo Step Into Big League 26 May 2021

The Week in Quotes 25 May 2021

Smashing Stats: Spain Masters 2021 18 May 2021

The Week in Quotes 17 May 2021

Spanish Reunion Ignites Rosengren 11 May 2021

A ‘Mixed Doubles’ Partnership for a Doubles Ace 8 May 2021

Momota Dwells on Sport for Social Change 6 May 2021

‘I Want Players to Think for Themselves’ 28 April 2021

The Week in Quotes 26 April 2021

Kim’s Fresh Approach After Relishing Club Challenge 25 April 2021

Despair to Delight – How Danes Turned it Around 24 April 2021

Resolute Kohli on the March Again 22 April 2021

The Week in Quotes 19 April 2021

Spectators to Competitors: Dream Comes True for ‘Inseparable’ Childhood Pals 18 April 2021

COVID Turns Nguyen Match-Savvy 15 April 2021

Ellatif, a Woman on a Mission 15 April 2021

Happy 90th, Poul-Erik Nielsen! 12 April 2021

AirBadminton: Healthy, Fun and More 7 April 2021

The Week in Quotes 6 April 2021

The Week in Quotes 29 March 2021

Magee Siblings Carry the Flag for Ireland 28 March 2021

The Week in Quotes 23 March 2021

Happy Ground England | Sukamuljo/Gideon 17 March 2021

Smashing Stats: YONEX All England Open 2021 17 March 2021

The Week in Quotes 15 March 2021

Hart Set on Super 1000 Debut 14 March 2021

Happy Ground England | Praveen Jordan 14 March 2021

Careme: Thom and Delphine Have Ingredients to be World’s Best 13 March 2021

‘We feel unstoppable’ 13 March 2021

Baptiste Careme: Trying to Individualise as Much as Possible 12 March 2021

Talented Indian Duo Bank on Danish Mastermind 11 March 2021

Aura of ‘Europe’s Best Pair’ Swells 10 March 2021

International Women’s Day: In Conversation with Pusarla V. Sindhu 9 March 2021

The Week in Quotes 9 March 2021

International Women’s Day: ‘Badminton is for Everyone’ 8 March 2021

International Women’s Day: ‘Setting an Example for Young Girls’ 8 March 2021

Kento Momota – Grit Over Despair 6 March 2021

Smashing Stats: YONEX Swiss Open 2021 2 March 2021

The Week in Quotes 1 March 2021

Breaking the Asian Wall 28 February 2021

Chan: Time to Show the World What We Can Do 23 February 2021

The Week in Quotes 22 February 2021

医者仁心,互相鼓舞 19 February 2021

The Week in Quotes 15 February 2021

Meet Ajaya Rana, ‘That Doctor in Blue Jacket’ 14 February 2021

Para Badminton Community Rejoices, Fire Reignited 13 February 2021

‘We Only Look at Each Other’s Eyes’ 12 February 2021

Asian Leg Review: Axelsen Rules the Court 11 February 2021

‘Great to be Back Playing Badminton’ 10 February 2021

The Week in Quotes 8 February 2021

Asian Leg Review: Upsets 7 February 2021

Asian Leg Review: Great Matches 6 February 2021

Smashing Stats: Bangkok Bonanza 3 February 2021

HSBC BWF World Tour Finals in Quotes 2 February 2021

TOYOTA Thailand Open in Quotes 25 January 2021

YONEX Thailand Open in Quotes 18 January 2021

YONEX Thailand Open: ‘A Perfect Birthday Gift’ 17 January 2021

Bangkok Diaries: Competition Eve 11 January 2021

Bangkok Diaries: Day 5 9 January 2021

Bangkok Diaries: Day 4 8 January 2021

Bangkok Diaries: Day 3 7 January 2021

Happy Ground Thailand | Chan/Goh 7 January 2021

Bangkok Diaries: Day 2 6 January 2021

Bangkok Diaries: Day 1 5 January 2021

The Week in Quotes 4 January 2021

Bangkok Beckons: January Like No Other 2 January 2021

Bye Bye 2020; Hello 2021! 1 January 2021

2020 in Review: Upsets of the Year 31 December 2020

2020 in Review: The Year in Quotes | Part II 29 December 2020

2020 in Review: The Year in Quotes | Part I 28 December 2020

Happy Ground Thailand | Chen/Jia 28 December 2020

2020 in Review: Farewell to the Stars 27 December 2020

2020 in Review: Viktor’s Delight 26 December 2020

Different Kind of Christmas 25 December 2020

Happy Ground Thailand | Chen Yu Fei 22 December 2020

The Week in Quotes 21 December 2020

Bangkok Beckons: Watch Out for Rasmus Gemke 20 December 2020

Happy Ground Thailand | Tommy Sugiarto 19 December 2020

On This Day: Eddy Kurniawan Seals Cult Status 16 December 2020

The Week in Quotes 14 December 2020

Beiwen Zhang – Adapting to Every Challenge 12 December 2020

Pusarla Happy With Progress During England Stint 8 December 2020

The Week in Quotes 7 December 2020

Jakob Hoi: ‘Just Pace Is Not the Way’ 6 December 2020

On This Day: Ge Fei-Gu Jun Break Susi Susanti’s Record 5 December 2020

Jakob Hoi: ‘I Can’t Sit Back and Be Impressed’ 3 December 2020

Video: Get to Know Jordan Hart 2 December 2020

More to Come from England 1 December 2020

The Week in Quotes 30 November 2020

English Badminton on the Right Track 26 November 2020

The Week in Quotes 23 November 2020

Clara Graversen: Badminton Gets a Spicy Kick 19 November 2020

Tai Tzu Ying Honing English Skills 19 November 2020

Australia’s Ma Salutes Resilient Human Race 17 November 2020

The Week in Quotes 16 November 2020

Video: Why Antonsen Did ‘The Cowboy’ 14 November 2020

On This Day: Quartet Create a Fuzhou China Open First 10 November 2020

The Week in Quotes 9 November 2020

Hall and Dunn on Highland Cows, Ice Hockey and Liverpool 8 November 2020

Yvonne Li: ‘Even on Vacations, My Family Would Play Badminton’ 7 November 2020

Books the Ideal Mental Health Remedy for Leydon-Davis 5 November 2020

Line Christophersen Makes the Right Moves 4 November 2020

‘Small Things’ Drive Ygor Coelho Forward 3 November 2020

The Week in Quotes 3 November 2020

Leonice Huet: ‘Paris 2024 is the Big Dream’ 1 November 2020

Young Danes Set Their Sights High 30 October 2020

Popov Brothers: On a Badminton Journey Together 28 October 2020

Lockdown Gives Lefel a Second Shot at Tokyo 27 October 2020

Jorgensen: Tenacious Battler on Court 26 October 2020

Top 5 Takeaways from DANISA Denmark Open 2020 26 October 2020

‘I’d Be Stuck at Home If Not for Para Badminton’ 24 October 2020

‘Every Team Concerned About Retaining Edge’ 23 October 2020

Our Players Are Back at Earlier Level: Park Joo Bong 21 October 2020

Denmark Open Passes Crucial Test With Flying Colours 21 October 2020

The Week in Quotes 20 October 2020

Denmark Open: Jordan Debuts With a Grateful Hart 15 October 2020

Smashing Stats: DANISA Denmark Open 2020 13 October 2020

The Week in Quotes 12 October 2020

World Mental Health Day: When Hall Refused to Fall 10 October 2020

World Mental Health Day: Why Badminton is Good for You 10 October 2020

On This Day: Badminton Becomes a Paralympic Sport 7 October 2020

Brian Kliwon: Umpire, athlete and future doctor 6 October 2020

The Week in Quotes 5 October 2020

Badminton Icon: Margaret Tragett 4 October 2020

Stars of the Past: Prakash Padukone 3 October 2020

Kiribati, the Only Nation to Play Badminton Across All Hemispheres 1 October 2020

Genius in Action: Candra Wijaya 30 September 2020

Shuttler of 2010s: Indonesia’s Natsir the Popular Choice 29 September 2020

The Week in Quotes 28 September 2020

Badminton Icon: Ralph Nichols 27 September 2020

Stars of the Past: Judy Devlin Hashman 26 September 2020

Badminton Quiz: Cheah Soon Kit 25 September 2020

Genius in Action: Cheah Soon Kit 23 September 2020

Women’s Shuttler of 2010s: Fans Go for Natsir 23 September 2020

Learn More About AirBadminton with New Video Series 22 September 2020

The Week in Quotes 21 September 2020

Badminton Icon: Ethel Thomson 20 September 2020

Badminton Quiz: Cai Yun & Fu Haifeng 18 September 2020

Genius in Action: Cai Yun & Fu Haifeng 17 September 2020

Men’s Shuttler of 2010s: Lee Chong Wei reigns 16 September 2020

The Week in Quotes 14 September 2020

Badminton Icon: Finn Kobbero 13 September 2020

Stars of the Past: Lee Wan Wah 12 September 2020

Badminton Quiz – Rexy Mainaky/Ricky Subagja 11 September 2020

‘It’s a New Era for the Team’: Kenneth Jonassen 10 September 2020

Genius in Action: Rexy Mainaky & Ricky Subagja 9 September 2020

The Week in Quotes 7 September 2020

Badminton Icon: Betty Uber 6 September 2020

Stars of the Past: Kenneth Jonassen 5 September 2020

Badminton Quiz: Lars Paaske/Jonas Rasmussen 4 September 2020

Genius in Action: Lars Paaske & Jonas Rasmussen 2 September 2020

Tokyo 2020: Paralympic Stars to Watch 1 September 2020

Shuttle Time at Home | Challenge 5: Calf Catching 1 September 2020

Badminton Icon: Frank Devlin 30 August 2020

Stars of the Past: Jwala Gutta 29 August 2020

Badminton Quiz: Ayaka Takahashi 28 August 2020

Genius in Action: Ayaka Takahashi 26 August 2020

Badminton Icon: Muriel Lucas 23 August 2020

Stars of the Past: Foo Kok Keong 22 August 2020

Badminton Quiz: World Championships 2019 21 August 2020

On This Day: When Lin and Lee First Contested an Olympic Final 17 August 2020

Badminton Icon: Sir George Thomas 16 August 2020

Badminton Quiz: Mia Audina 14 August 2020

Genius in Action: Mia Audina 12 August 2020

The Week in Quotes 11 August 2020

Stars of the Past: Susan Devlin Peard 10 August 2020

Badminton Icon: Judy Devlin 9 August 2020

Badminton Quiz: Camilla Martin 7 August 2020

Genius in Action: Camilla Martin 5 August 2020

The Week in Quotes 4 August 2020

Badminton Icon: Zhao Yunlei 2 August 2020

Stars of the Past: Thomas Kihlstrom 1 August 2020

Badminton Quiz: Ge Fei & Gu Jun 31 July 2020

Barbara Fryer the High-Flyer Makes It a First 30 July 2020

Genius in Action: Ge Fei & Gu Jun 29 July 2020

Shuttle Time at Home | Challenge 4: Balance The Racket 28 July 2020

The Week in Quotes 27 July 2020

Stars of the Past: Xu Huaiwen 26 July 2020

Badminton Quiz: Tony Gunawan 24 July 2020

Badminton’s Most Successful Olympians 23 July 2020

Genius in Action: Tony Gunawan 22 July 2020

‘I’m Excited and Nervous’: Chau Hoi Wah 21 July 2020

The Week in Quotes 20 July 2020

Stars of the Past – Pi Hongyan 18 July 2020

Badminton Quiz: Carolina Marin 17 July 2020

Genius in Action: Carolina Marin 15 July 2020

The Week in Quotes 14 July 2020

Icy Alaska Goes Wild for Badminton 12 July 2020

Team Japan is Back on Court 11 July 2020

Badminton Quiz: Lin Dan 10 July 2020

Lin Dan – An Appreciation 9 July 2020

Shuttle Time at Home | Challenge 3: Balance & Throw 9 July 2020

Mogensen’s Forte Was His Tactical Acumen 8 July 2020

Genius in Action – Kim Dong Moon 8 July 2020

The Week in Quotes: Lin Dan Tribute Special 6 July 2020

Lin Dan – Greatest Title Wins 5 July 2020

Lin Dan Calls It a Day 4 July 2020

Badminton Quiz: Olympics (1996-2004) 3 July 2020

Shuttle Time Trumps Regular PE, Says Study 2 July 2020

Genius in Action: Koo Kien Keat & Tan Boon Heong 1 July 2020

The Week in Quotes 29 June 2020

Did You Know? Doubles Star Taerattanachai Has a Singles Title 28 June 2020

Badminton Quiz: Early Olympic Years 26 June 2020

Genius in Action: Ratchanok Intanon 24 June 2020

On This Day: Jorgensen Makes Europe Stand Tall in Indonesia 22 June 2020

The Week in Quotes 22 June 2020

Video: Lockdown Can Be Fun 21 June 2020

Refugee Athlete Mahmoud Resilient Despite Lockdown Blues 20 June 2020

Badminton Quiz: Rudy Hartono 19 June 2020

Genius in Action: Lin Dan 17 June 2020

Time for Self-Reflection, Says Greysia Polii 16 June 2020

The Week in Quotes 15 June 2020

‘Dad Feared Letting Me Play Badminton’ 14 June 2020

Suits and Stages: Greenland Duo Rocking New Gigs 13 June 2020

Badminton Quiz: Indian Icons 12 June 2020

Genius in Action: Saina Nehwal 10 June 2020

Shuttle Time at Home | Challenge 2: Backhand Low Serve 9 June 2020

Badminton Quiz: Tai Tzu Ying 5 June 2020

Genius in Action: Tine Baun 3 June 2020

Badminton Triumphs Trump Cricket Dreams for Tarun Dhillon 2 June 2020

The Week in Quotes 1 June 2020

Pandemic Spurs Pak to Pick Up Sixth Language 31 May 2020

Marcus Ellis | Part II: Homing in on Success 30 May 2020

Badminton Quiz: Japanese Icons 29 May 2020

Genius in Action: Gao Ling & Huang Sui 27 May 2020

Marcus Ellis | Part I: Our fittest athlete? 26 May 2020

Badminton Quiz: Thomas & Uber Cup Finals 23 May 2020

Getting to Know … Daniel Bethell 20 May 2020

The Week in Quotes 19 May 2020

Shuttle Time at Home | Challenge 1: Balloon Tap 19 May 2020

‘Time for Development, but Aware Monotony Can Set In’ 16 May 2020

Badminton Quiz: Para Badminton Icons 15 May 2020

Away From Puzzling Opponents, Tai Works on Jigsaw 14 May 2020

Genius in Action: Susi Susanti & Bang Soo Hyun 13 May 2020

Hungry Marin Hunting ‘Greatest Ever’ Tag 12 May 2020

The Week in Quotes 11 May 2020

Sukant Kadam: How I Started Playing Badminton 10 May 2020

Badminton Quiz: World Superseries 8 May 2020

Taliban Attack Survivor Won’t Slow Down Just Yet 8 May 2020

Star Creation Programme Delivers ‘New Stars’ 7 May 2020

Genius in Action: Lee Chong Wei 6 May 2020

Food for Needy: PNG Badminton Community Steps Up 6 May 2020

Life in Lockdown: Training, Hobbies, Family 5 May 2020

The Week in Quotes 4 May 2020

‘The Break is Nice… But It’s a Little Too Long!’ 2 May 2020

Badminton Quiz: English Icons 1 May 2020

Antonsen’s Vlog Offers a Close View of Athlete Life 30 April 2020

Genius in Action: Mathias Boe & Carsten Mogensen 29 April 2020

On This Day: Special Feat Announces Intanon’s Arrival 28 April 2020

The Week in Quotes 27 April 2020

Tips on Handling Isolation, From Badminton-Playing Cosmonaut 25 April 2020

Badminton Quiz: HSBC BWF World Tour 24 April 2020

Lockdown Highs and Lows 23 April 2020

Genius in Action: Tontowi Ahmad & Liliyana Natsir 22 April 2020

The Week in Quotes 21 April 2020

PNG Teen Ready to Fly High After ‘First Plane Trip’ 19 April 2020

RIP Louis Ross, Master of Badminton Photography 19 April 2020

Choong Hann Underlines ‘Value Add’ During Lockdown Training 18 April 2020

Badminton Quiz: Indonesian Icons 17 April 2020

Farewell to a Badminton Impresario 17 April 2020

Genius in Action: Lee Yong Dae 15 April 2020

With Willpower and Great Dedication Comes Vitor Tavares 14 April 2020

The Week in Quotes 13 April 2020

On This Day: India Toasts First Men’s Singles World No.1 12 April 2020

Badminton Quiz: Highlights of 2019 10 April 2020

Online Sessions, Smartwatches: Thai Players Train in Lockdown 9 April 2020

Genius in Action: Zhao Yunlei & Tian Qing 8 April 2020

Teitiria and Tinabora – Kiribati’s Perfect Badminton Role Models 8 April 2020

The Week in Quotes 7 April 2020

Study Sheds More Light on Jump Smash 2 April 2020

Genius in Action: Taufik Hidayat 1 April 2020

Sports Science Keeps Gronya Bouncing Alright 31 March 2020

The Week in Quotes 30 March 2020

Thanks to Badminton, Adversity’s a Friend to Gaitan 29 March 2020

Positive Blichfeldt ‘Will Give Anything’ to Play Again 28 March 2020

Genius in Action: Li Xuerui 26 March 2020

On This Day: World Junior Champs Win Only Senior Title 21 March 2020

The Week in Quotes 9 March 2020

International Women’s Day: BWF’s Focus On Gender Equity 8 March 2020

The Week in Quotes 2 March 2020

Resolutions for 2020, and Beyond… 16 February 2020

PNG’s Para Players Set to Showcase Skills 10 February 2020

Bound for Big Things – Road to Tokyo: Krishna Nagar 8 February 2020

Dong Jiong: A Champion of Change (Part 4) 23 January 2020

A Leap Up for Thygesen & Fruergaard 22 January 2020

From Myanmar, Destination Tokyo 7 January 2020

2020 and Beyond – Some Top Prospects 6 January 2020

Dong Jiong: A Champion of Change (Part 3) 3 January 2020

Five Memorable Matches of 2019 1 January 2020

A Year In Review 31 December 2019

Five Surprise Title Wins of 2019 30 December 2019

Dong Jiong: A Champion of Change (Part 2) 28 December 2019

Dong Jiong: A Champion of Change (Part 1) 24 December 2019

Top Five Records of 2019 22 December 2019

Tokyo Legends Inspiring Current Stars 21 December 2019

Johan Wahjudi, a Pioneer in Men’s Doubles 20 November 2019

Kim Gives Kajiwara Four Years – Japan Para Badminton International 2019 16 November 2019

Big in Tokyo – Japan Para Badminton International: Day 1 13 November 2019

Might of Mind Over Matter – Road To Tokyo: Valeska Knoblauch 5 November 2019

World Juniors Showcases Growth of Badminton 31 October 2019

A Great Sport for Building Morale 11 October 2019

Cosmonaut Says Badminton Ideal for Space Crews 10 October 2019

World at the Doorstep 7 October 2019

History for Tahiti Juniors 7 October 2019

Should We Have Ever Doubted? 26 September 2019

Ray’s a Real Sport – 25th Edition World C’Ships 25 August 2019

Flaming Dane Set Courts Aglow – 25th Edition World C’Ships 24 August 2019

Crowd Pleasing Superstar – 25th Edition World C’Ships 23 August 2019

Badminton Fan Gets Her Wish 22 August 2019

Genius of Vintage Invincibles (Part 2) – 25th Edition World C’Ships 13 August 2019

Genius of Vintage Invincibles (Part 1) – 25th Edition World C’Ships 12 August 2019

Born Fighter – Road To Tokyo: Tim Haller 6 August 2019

Plenty To Learn Say Lee and Chochuwong – Thailand Open: Semifinals 3 August 2019

At the Height of His Career – Road To Tokyo: Lucas Mazur 16 July 2019

Badminton Saved My Life – Road To Tokyo: Chan Ho Yuen 5 July 2019

Coach on a Mission 2 July 2019

Para badminton and BWF Shuttle Time Making Waves in Fiji 1 July 2019

Determined Penty Seeks Success in Minsk 21 June 2019

Lee Chong Wei – A Model of Consistency 14 June 2019

Key Moments: Chen vs. Yamaguchi – Sudirman Cup ‘19 30 May 2019

What We Have Learned – Road To Tokyo 29 May 2019

Pathway to Success for Kazakhstan – Sudirman Cup ’19 21 May 2019

Chinese stars endorse AirBadminton 16 May 2019

Insights into the New AirShuttle 15 May 2019

7 Things You Need to Know About AirBadminton 14 May 2019

BWF Encourages ‘Sport For All’ Through Charity Coaching Clinic 6 April 2019

Badminton House: Where It All Started 20 March 2019

BWF Shuttle Time Graduates Debut on the Big Stage 14 March 2019

Scene Set for Intriguing All England 5 March 2019

Online English Language Learning for Athletes 27 February 2019

Badminton Still No. 1 for Sri Lankan Cricket’s Latest Debutante 6 February 2019

BWF’s Health Study to Address Injury Concerns 17 January 2019

Zheng & Huang – Will the Spell Hold? 10 January 2019

Thailand Masters Kicks Off Action-Packed Season 7 January 2019

All Set for Generational Battles in 2019 2 January 2019

Many Arrows in the Quiver for China, Japan 25 December 2018

Kenneth Larsen Pitches for Reflective Training 18 November 2018

Kento Momota Completes Ascent 27 September 2018

Farewell, Jung Jae Sung 10 March 2018

Badminton Personality Hansen Passes Away 22 January 2018

Welcome to Glasgow! 19 August 2017

Star Pairs Perish – Day 2: BCA Indonesia Open 2017 13 June 2017

Tai Rakes in the Big Bucks 6 May 2017

‘I Hope to be Consistent’: Tai Tzu Ying 3 May 2017

Tan/Setiawan Hope to Hit the High Notes 16 March 2017

Sung Energised by Recent Successes 1 March 2017

Line Kjaersfeldt Targets GPG Success 20 February 2017

‘Upwardly Mobile’ Thais Aim for Top 5 27 January 2017

Saina Nehwal: ‘I Feel Lighter On Court’ 20 January 2017

Zwiebler Hungry Despite Setbacks 18 January 2017

Yamaguchi Looks to Build on 2016 Successes 16 January 2017

Saluting Long-Serving ‘Family’ 22 November 2016

Farewell ‘Ma-gnificent’ Jin! 21 November 2016

Development Pioneer ‘Very Proud’ 9 November 2016

Champion Retires to Classroom 14 October 2016

Charismatic Champ Bows Out 5 October 2016

Lee Yong Dae: ‘Retirement Decision is Final’ 29 September 2016

Rio Countdown: Australian Duo Look to Make Impact 26 July 2016

Rio Countdown: Chou Riding High on Confidence 25 July 2016

Mogensen’s Back and Raring To Go! 30 May 2016

Liang Xiaoyu Sniffs Olympics Chance 15 March 2016

Labar and Lefel Seek Superseries Push 4 March 2016

Intanon Ready for Battles Ahead 2 March 2016

Identical Twins, Dual Personalities 24 February 2016

Ahmad/ Natsir Confident of Shaking Off Slump 16 February 2016

Jayaram Hopes to Build on Bright 2015 9 February 2016

Wang Backs Herself with Rio on Horizon 5 February 2016

‘I’m More Mature Now’: Chau Hoi Wah 28 January 2016

My Family is My Inspiration: Joachim Fischer Nielsen 22 January 2016

Every Match is Like a Final: Nozomi Okuhara 20 January 2016

We Help Each Other: Lee & Yoo 20 January 2016

Men’s Singles – 2015 in Review 30 December 2015

Tai Happy Despite Diminishing Returns 11 December 2015

Leverdez Struggles With News of Tragedy 18 November 2015

Sindhu Ousts Mighty Marin – Day 5: Yonex Denmark Open 2015 17 October 2015

Michelle Li: ‘I Want to Change the Sport in North America’ 9 October 2015

100 Days Countdown: World Champions Eye Dubai Finale 31 August 2015

Survivor Ekiring Has Ambitions for Africa 12 August 2015

Outgoing Players’ Rep Reflects 11 May 2015

Beiwen Zhang: Pursuing Dreams Single-Mindedly 7 April 2015

Conrad-Petersen: Ten Months to Self-Discovery 1 April 2015

In-form Jorgensen Wary of India Open 2015 Minefield 24 March 2015

World of a Battle for No.1 20 March 2015

Patience Pays Off for Vittinghus 22 December 2014

Luo Twins Relish ‘Double’ Identity 18 December 2014

Hopefuls Pushing the Boundaries 5 September 2014

Bonding through Badminton 26 August 2014

Ygor Oliveira’s ‘Sun-rise’ Moment 25 August 2014

Robertson, Cheng Spread Badminton Gospel 20 August 2014

Youth Olympic Games 2014 – Day 1: Mixed Doubles Steals the Show 17 August 2014

Saluting Søborg – Trailblazing Badminton Photographer 14 November 2013

Remembering Jørgen Hammergaard Hansen 6 September 2013

RedBull China Scores Big With “Super Final” 27 August 2013

Badminton Talent Dies in Accident 15 August 2013